New book offers a guide for building library collections and curriculum centered on Indigenous works

The University Libraries’ Indigenous book and film collection began with a purchase request from Javier Muñoz-Díaz, assistant professor of Spanish at Farmingdale State College. At the time, he was a CU Boulder student pursuing a PhD in Spanish when he noticed a lack of Indigenous authors in the Libraries’ collection. The collection has now grown to include hundreds of items by Indigenous peoples thanks to Romance Languages Librarian Kathia Ibacache.

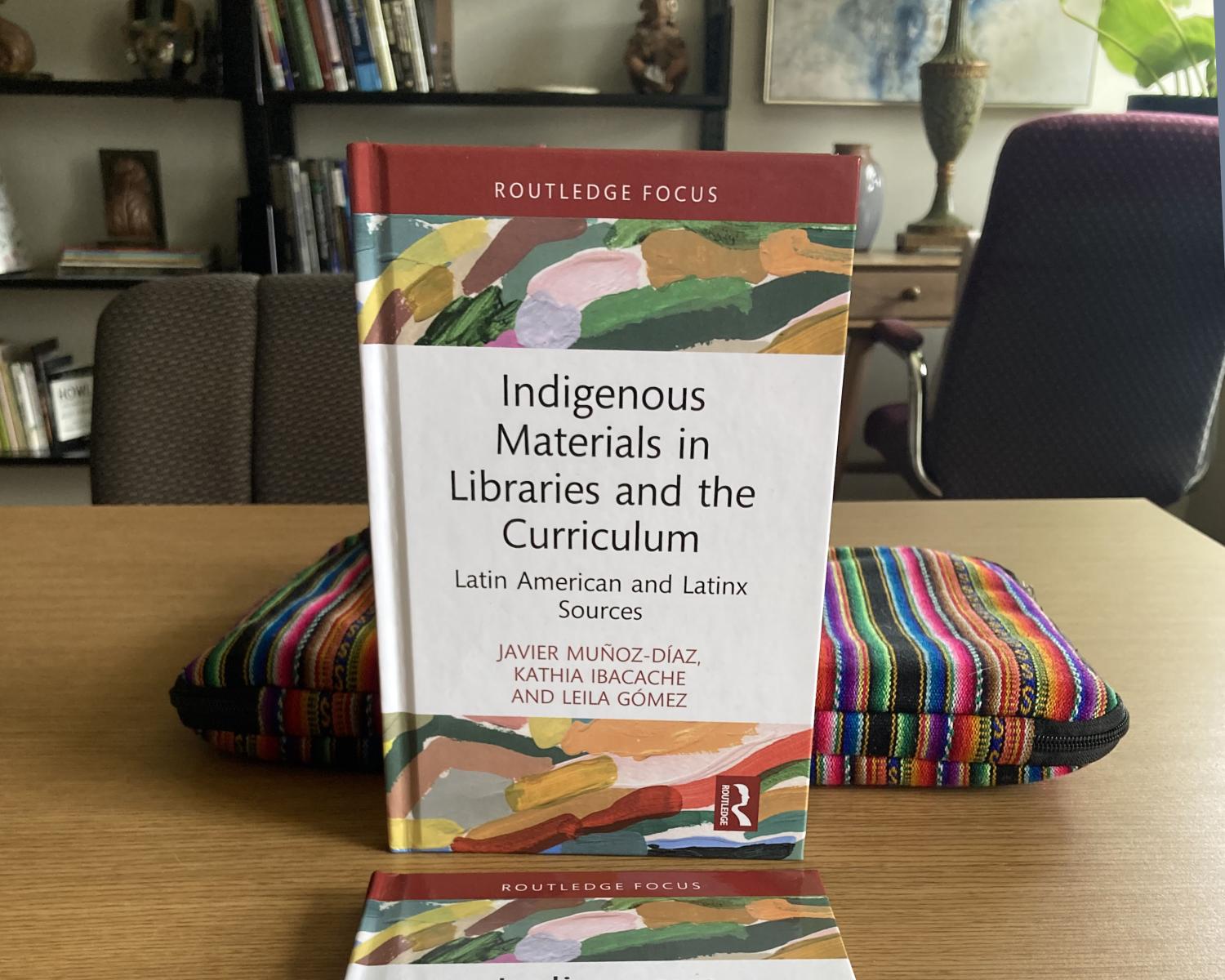

Now, together with Professor Leila Gómez in the Department of Women and Gender Studies at CU Boulder, Ibacache, Muñoz-Díaz and Gómez have co-authored a new book entitled Indigenous Materials in Libraries and the Curriculum Latin American and Latinx Sources about how faculty and librarians can collaborate to develop inclusive library collections and curricula by supporting Indigenous peoples' reclamation of lands and languages.

Ibacache, Gómez and Muñoz-Díaz discussed what led to the creation of this collection and the publication of the book.

Tell me about the book. How did your collaboration with co-authors Javier Muñoz-Díaz and Leila Gómez begin?

Ibacache: I met Javier in 2019. I was surprised to see his great engagement with the Spanish and Portuguese collections. In one of our conversations, he noted that our collections were missing books written by Indigenous authors from Latin American regions. I had been appointed the Romance Languages librarian at the end of 2018; therefore, I found this revelation compelling and became the seed for my interest and work in growing a collection of books authored by Indigenous authors or addressing topics from an Indigenous agency. Similarly, Leila was one of my constituents then, particularly when she became director of the Latin American and Latinx Studies Center in 2017. Our collaboration strengthened when she created the Quechua Program at CU Boulder thanks to a Department of Education grant (Title VI). Her areas of expertise are Latin American and Indigenous literature and culture, and she created a curriculum that advanced this area of knowledge.

How did the collection start, and what are some items that you would like to highlight?

Ibacache: My interest in building a collection representative of Indigenous knowledge and Languages from Latin American regions started thanks to Javier’s revelation in 2019. This year, I received an IMPART award that supported a conference presentation based on my research examining library holdings in seven Indigenous languages (Quechua, Nahuatl, Guaraní, Zapotec, Maya, Mapudungun and Aymara) in 87 university libraries in the US. This award also prompted me to support an undergraduate course. Leila’s course Gender and Indigeneity in Latin American Literature and Film, offered at CU Boulder in the fall of 2020, had great importance because I wanted to support this course with the collection.

By 2024, the Indigenous Knowledge and Languages from Latin America collection has significantly grown to feature films, documentaries, fictionalized documentaries and a wide array of books—informational, poetry, short novels, tales (cuento), and even books for the Children and Young Adult Collection. One film license that I would like to highlight is the fictionalized short documentary Yalø pøñinkau (Mariposa Negra /Black Butterfly) by Misak director Luis Tróchez Tunubalá with English captions. This film artistically and compellingly directs our attention to sexual violence against a young adult Indigenous woman, helping us reflect on the clash between Indigenous cosmovision and identities with that of the dominant society. A book of horror tales in Quechua and Spanish called “Pesadillas” (Mancharikuypaq : Musquykuna runasimipikastillanusimipi mancharikuypaq willakuykuna) in Spanish and Quechua translated by Luis Alberto Huamaní is another powerful book of fiction that connects readers to the tale genre for adult readers, a genre where authors from Latin America excel.

Gómez: We also highlight the books and films by Indigenous creators who came to CU Boulder. We invited several of the authors whose books and films Kathia bought for the Indigenous collection to CU Boulder to present their work as part of the Quechua Program events and classes. For example, the Quechua poet Gloria Caceres read and talked about her poetry in our classes, the Quechua Program, and in Women and Gender Studies. The director of the film Mama Irene, Healer of the Andes, Elisabeth Möhlmann, and the healer’s granddaughter, Magaly Qispe, also joined a discussion with students about the ancestral knowledge and practice of Indigenous women healers.

Ibacache: Our book emphasizes the value of multilingual materials in collections, especially those with English translations that may open a window for students to learn about the literary traditions, cultures and expressions connected to the creative output of Indigenous authors and those who offer works addressing Indigenous agency.

Kathia Ibacache, associate professor and romance languages librarian

Who is the audience for this book? Can disciplines outside of Latinx and Indigenous studies use this as a guide to building collections and teaching with Indigenous materials?

Ibacache: The audience is academic, but our book could also support public and special libraries, especially if these types of libraries seek to build an Indigenous collection. Our book developed thanks to an interdisciplinary cooperation between librarian and faculty. The base of our collaborative work as faculty and librarian is transferable to other areas, especially those that may enrich their curricular and collection canon with Indigenous epistemologies that consider language, culture, perspectives, expression and agency, for example. I am considering academic units such as Women and Gender Studies, Anthropology, Cinema Studies, History, Philosophy, Religious Studies, Ecology, Environmental Studies and Ethnic Studies.

In the book, Muñoz-Díaz and Gómez detail how they use the collection in coursework. How are students engaging with it?

Muñoz-Díaz: Most students have been very receptive to course materials that showcase Indigenous peoples’ agency and perspective. Gen Z students are generally attuned to social justice issues, so we want to build on the momentum and bring awareness about students' positionality regarding Indigenous rights. As instructors, we always highlight that indigeneity not only pertains to ethnicity or race but is intersected and entangled with issues of land and environmental rights, social class and economic inequality, and gender and sexual diversity, among others.

For instance, in the book’s fourth chapter (“Indigenizing Feminins in the Classroom”), Leila Gómez and I outlined how to engage with the work of Indigenous women fighting for land and environmental justice. We use bilingual and multilingual materials (such as the feature film Ixcanul and the documentary Mothers of the Land), which not only challenge gender stereotypes but also open opportunities to discuss alternative epistemologies about our relationship with the territory and the natural world. On the other hand, a feature film such as Retablo shows students how homophobia in Indigenous communities is connected with larger structures of colonialism. Finally, we address the relevance of Indigenous struggles in a global context by showcasing the commonalities among Indigenous peoples from Latin America and Native Americans and First Nations from North America. A guiding principle in this regard is the K'iche' Maya scholar Emile Keme’s proposal of Abiayala (the Guna People’s name for the American continent) as a locus of political enunciation for Indigenous peoples in their opposition to extractive capitalism and state-sponsored violence. In our teaching and course design, we modestly aspire to be allies to the empowerment of Indigenous communities, which are still facing widespread oppression and marginalization. This is why our book starts on a somber note, acknowledging the alarming numbers of Indigenous activists for land and environmental rights murdered in recent years.

Leila Gómez, associate professor in the Department of Women and Gender Studies

What is your recommendation to faculty members and instructors who are interested in incorporating Indigenous knowledge into their course work but who may not know where to begin or have the institutional support?

Muñoz-Díaz: We recommend contacting Indigenous peoples directly and asking them how they can collaborate and support each other. Indigenous people are still working outside mainstream or institutional channels, so we need to go the extra mile to reach them in their communities. Fortunately, the internet and social media have facilitated this process. Additionally, Leila Gómez and I included in the book’s third chapter, “How to Decolonize and Indigenize the Curriculum,” an indictment of the structural Eurocentrism in Spanish language teaching and Latin American studies programs, which still neglect the life experiences and perspectives of Indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups, including the Latinx diaspora in North America. We offer our experiences navigating the scaffolding of higher education at several levels—designing course materials for a specific class, creating new courses about indigeneity, and developing teaching programs for Indigenous language with the Quechua program at CU Boulder as an example.

Relationship building is a key theme in this book—from starting this collection by building a relationship with a PhD student and faculty member to building relationships with publishers and authors to creating a decolonization framework—how can faculty and librarians start to have these kinds of conversations and build these kinds of relationships within their institution and outside of it?

Ibacache: Yes, relationship building is an essential theme in the book. Our book journey materialized because of this relationship. Similarly, building relationships with publishers, authors, and book vendors is at the core of intentional collection development responsibilities. This type of relationship-building also shows the faculty’s commitment and engagement. I mention the adjective “intentional” because establishing these connections means looking for these parties and approaching them. I know of faculty who know authors and film directors, sharing these contacts with librarians. Building these professional relationships means that we actively look for authors and non-mainstream publishers. I agree with Javier when they note that social media and the Internet are a path to connect with Indigenous peoples directly and establish collaboration and engagement.

Gómez: One key aspect of this relationship-building was inviting Indigenous artists and creators to CU Boulder. Through the Celebrating the Indigenous Americas Week, a whole week of panels, roundtables and performances, co-organized by the Quechua Program, the University Libraries, and several other departments in 2021, 2022 and 2024, we were able to welcome Indigenous artists, activists, scholars, educators and connect with their work as a community. This is part of the decolonial framework we discussed in our book, which seeks to create institutional spaces to engage in conversations with Indigenous knowledge and creators, not about them.

Javier Muñoz-Díaz, assistant professor of Spanish at Farmingdale State College

The book puts emphasis on the distinction between "about" vs. "by/with" Indigenous people. How did you start to define an Indigenous collection when identity is so complex?

Muñoz-Díaz: It is difficult to define “Indigenous,” given the heterogeneity of life experiences that claim such a label and the intrinsically conflictive nature of any issue pertaining to identity politics. For that reason, in the book’s introduction, Leila Gómez and I decided to follow a political definition of indigeneity rather than a cultural/identitarian one. We place indigeneity within the struggle for land and environmental rights against extractivism. “Extractivism” is a term we understand in a material sense (the destruction of nature for the plundering of raw materials) and in a symbolic one (the appropriation of Indigenous peoples’ life experience by non-Indigenous peoples who write on behalf of them without their permission). Following this thread, the distinction between “about” vs. “by/with” speaks about the necessity to center the coursework on people’s voices and perspectives directly affected by the interlocking system of oppression that marginalizes the land's original inhabitants. Some materials might be produced entirely by an Indigenous community for the benefit of its members. In contrast, other materials might result from a collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous. We encourage our students to critically engage with both kinds of materials.

Ibacache: Examining the distinction between “about” and “by/with” Indigenous people was part of our conversations during our meetings, and the book addressed this conflict, which is especially noticeable in library materials such as books and films. For collection development, the section “Inclusive Selection Criteria” in chapter one, offers a useful overview of the many nuances librarians will encounter when selecting these materials and that librarians should consider for true inclusive collection development. It is not a matter of purchasing a book with a title that makes us think this item must be “Indigenous.” It is a matter of intentionally assessing the content of the materials, looking for creators that identify as Indigenous authors, film directors and producers, etc. or that, without being Indigenous, create content from an Indigenous point of view of where Indigenous people have complete control over their stories.