Newly donated Asian maps bring exciting scholarship opportunities to CU

A donation of historical Asian maps from a local collector to the University Libraries is opening new opportunities for Asian studies scholars.

Donated as a group by map collector and CU Boulder alumnus, Wes Brown, these Chinese and Japanese maps represent diverse historical and cultural contexts. University librarians who are Asian-studies specialists translated and investigated the maps, uncovering meaning and raising questions for further research.

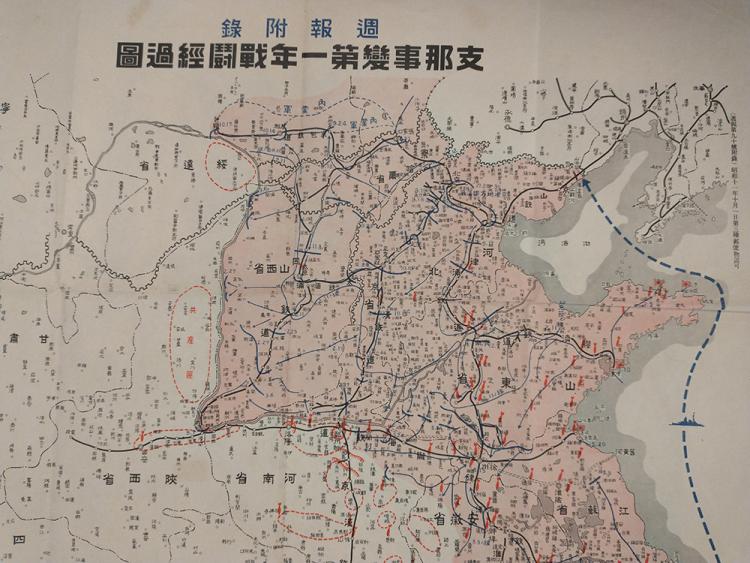

Japanese and Korean Studies Librarian Adam Lisbon worked with some of the Japanese maps, which consisted of a 1920 Japanese guide to Beijing and surrounding area; a 1930 Buddhist pilgrimage of Japan; and a 1938 World War II military map.

The military map raised questions for Lisbon. The date and publication on the right side of the map read, “(Weekly Report 90 Attached) 1936, October 1st.” The landing spot indicated on the map is of the city depicted. The Japanese army had already occupied Manchuria since 1931 and the Lugou Bridge Incident, also known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which began the Japanese invasion of the entirety of China, would not happen until July 7, 1937.

Lisbon observed, “The document is dated for October of 1938, which leads me to assume this is a recap of invasion tactics. The maps open more lines of inquiry, who are they intended for? How many were produced?”

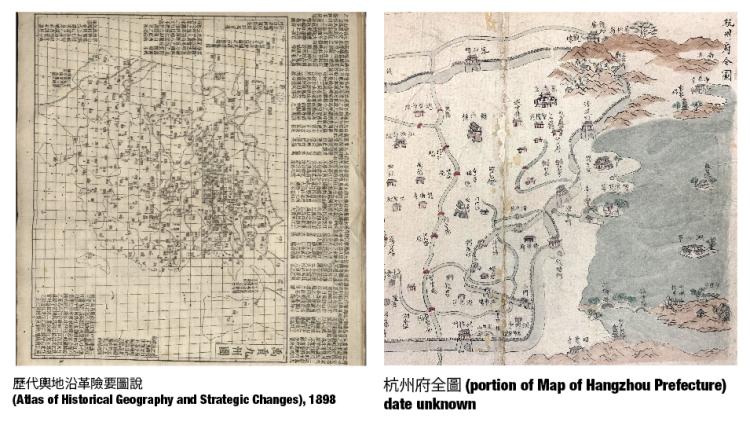

Among the donated Chinese maps, studied by Chinese and Asian Studies Librarian Xiang Li, is a hand-painted map that references Shengjing, which Li noted is the name used between 1634 to 1907 for what is now Shenyang. With reference to Google maps, it is possible to see that the shape of the river depicted on the historic maps is still evident in what is now a city of some 8.2 million people.

Li noted that, “The Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties have left us with an abundance of maps. However, only a small fraction of these have been thoroughly studied and documented, making it difficult to pinpoint the exact dates of many maps.”

In addition to the difficulty of dating maps of this period, the sharp distinction between cartography and landscape painting that exists in the western tradition is not so clear cut in Chinese representations of land and space. Chinese maps usually lack scale, grid and other quantitative data. Li noted that, “research into Chinese cartography history shows that although both pictorial and mathematical mapmaking existed, pictorial representations became dominant.”

Li cited Professor Cordell D.K. Yee’s argument that the understanding of space in Chinese culture as dynamic and fluid has led to a different treatment of perspective in Chinese cartography and painting than in European arts. The observer standpoint is not fixed but multiple, closely related to one’s experience of time.

“Through these maps, one can trace the evolution of social structure, economic developments, scientific advancements, philosophy and values that are all intertwined with the art and science of mapmaking” said Li.

“These maps open areas of scholarly inquiry that may not have been available before their donation,” said Li. “It’s exciting to think about the opportunities for scholars, both at CU and at other research institutions.”

Lisbon agrees. “Without this generous donation from Wes Brown, researchers may never have had access to such important cultural documents.”

Browsing the map collection is highly encouraged! If you would like to use maps as a primary source in your next creative or scholarly project:

Contact rad@colorado.edu to schedule an appointment, or drop by the Earth Sciences & Map Library Monday through Friday between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. to find map librarians Ilene Raynes and Naomi Heiser.